This article was originally written in about 2001 by my husband Ed Pretty, Battalion Chief and career firefighter. He has asked me to post it. The “Who Are We?” he makes reference to at the end was written by anonymous.

“Help me!” “Help my husband! He’s buried! He’s turning blue, he’s turning bluuue!”

These were the screaming word’s that greeted my dispatcher’s ears as she barely got out the standard “Fire Department Emergency.” In listening to the tapes later, I could feel the woman’s anguish and helplessness. Her plea for help cut to the bone. This is not a story about the woman who did all she could to help her husband trapped upright in a hand-dug trench.

As a Battalion Chief, my office adjoins the dispatch center and although I am typically not “tapped out” for rescues, the one side of the dispatcher’s phone conversation caught my ear. Entering the room, I heard more of the conversation as the units were being dispatched and the call-taking dispatcher attempted to calm the woman and at the same time get more information out of her. “…eight feet deep? … the wall has collapsed? … are your kid’s there ma’am? …uh huh, the trucks are coming already… please calm down, ma’am, I can give you more help if you help me …that’s better … how much of the wall has collapsed?” All the time, during the conversation, information is updated and typed into the computer by the call-taker to be passed on to the responding units by the dispatcher. As I listened to the information come in I realized this rescue would require considerable more and different resources than most rescues. The on-scene officers would be overwhelmed and I should be there to fill the roll of Incident Command to relieve them for the tactical duties they would have to perform. I left the room saying over my shoulder, “Put me on the call and get me a backhoe…code three.” This story is neither about me nor how the rescue scene was organized.

Upon arrival I found organized chaos with first arriving Fire, Ambulance and Police personnel on scene. Firefighters in and around the trench were placing shoring to stabilize the area so that rescue efforts would not cause a further collapse. Ambulance personnel were waiting anxiously for the go-ahead to get in and provide stabilizing medications and oxygen to the victim during the extrication. Police were controlling the crowd and were organizing their Victim Services personnel to assist with the family. The firefighters in the hole were then working feverishly; scratching at an incredibly hard block of clay, the size of a small car, that had tipped sideways onto the victim and had him pinned. Using every tool and trick in their bag, they were frustrated at every turn. The most they could achieve was to use special air bags to push the block slightly and gain a breathing space to at least buy time for the further effort that would be needed. Their training, savvy and ingenuity was being pressed to the limit and time was getting short as the victim was slowly becoming hypothermic and shocky. CEO’s would do well to learn from the well-implemented management processes that take place at such an incident. This story is not about the well-trained and experienced people that worked together to save this man’s life that day.

This story is about the unseen dispatcher who got the backhoe there in time that ultimately saved the man’s life. On a sunny Sunday afternoon. Code three using a police escort. This is the same backhoe that was requested with an over-the-shoulder order to a dispatcher in the middle of a phone conversation with a panic-stricken woman, who, at the same time, was typing virtually every word of their conversation into a computer. Of all the apparent heroic deeds performed that day, the one thing that saved the man’s life was the backhoe. All other efforts proved to be futile, and the timeliness of its arrival is what made the difference. The news crews interviewed myself as well as the grubbiest (good looking) firefighter. They filmed the backhoe working ever so carefully during the extrication and the ambulance personnel wheeling the victim to the ambulance. They were literally clambering over one another to get footage and interviews from the apparent heroes but they missed the mark completely because the heroes weren’t even at the scene; they were back in Dispatch. No one interviewed the dispatchers nor filmed them as they worked; yet they are the ones who found a backhoe operator on a sunny Sunday afternoon and coordinated the police escort to get the one piece of equipment on scene that truly saved the man’s life.

Trying to make the incident more marketable, the reporters asked me if I felt this was a dramatic rescue. Rescues aren’t dramatic; frantic, methodical or tedious maybe, but not dramatic. If they wanted real drama, the Dispatch Center was the place to be. Watching peoples’ gut wrenching emotions as they continue their work, not knowing if they have done enough; feeling the tension of waiting without the immediate visual clues to success or failure. Constantly the questions, “I wonder how it’s going?” is spoken through words and glances during moments of silence on the radio. During this incident, but not all, there is the exultation when the critical piece of equipment arrived that will turn the tide. But then silence again. You feel the tension as if it was a physical thing and it continues until the transmission, “Dispatch, Command is terminated and all units are returning.” Did they get him out alive? Is the wife OK? Only the experienced Dispatchers know the outcome was at least positive because no one requested the coroner. But still o real answers unless they get a chance to talk to the company officers sometime later. During all of this, the phones never stop ringing and incidents, both critical and ludicrous, continue.

Dispatchers are the very first responders

Dispatchers are the very first responders in any emergency organization and they are often overlooked; unfortunately, even by their peers on the front lines. Nine-eleven is a day that is fixed in anyone’s mind old enough to comprehend the significance of the event. Peoples’ visions are of dusty survivors, exhausted firefighters, harried policemen and awe-struck onlookers. No one, except dispatchers or those close to them, would even think of the dispatch workers in those agencies. In all cases, there would have come a time when they absolutely knew they were sending their coworkers to their certain death. To try to raise a unit on-air that is not responding is gut wrenching until that unit responds. To try to raise a unit and not have it respond is crushing. It is inconceivable to comprehend the feeling when unit after unit were just simply…gone. Some of them would have been knowingly sending friends and even family to the the fray. As overwhelming as the event was, life went on and the City would still have to respond to everyday emergencies, and the dispatcher would have to keep their focus through the mayhem so that no one went without help. To a lesser degree, that sort of thing happens every day in Everytown. Dispatchers send units staffed by coworkers, friends and even family members to calls, knowing the danger they face on arrival, and do it routinely as they get set up for the next call.

“If it’s so bad, then why do they keep doing the job?”, you say. Why do any of us do what we do? “To keep the light on” is one answer that we all use when being flippant. But emergency services, dispatchers included, the reason goes to the core of who we are as people. The satisfaction of being able to help and make a significant positive difference in peoples’ lives is tremendous. That need to do well for people is strong in all of us, and having the opportunity to fulfill that need in spite of the hardships, is what keeps us all there.

If dispatchers were asked to make a list of those things that attract them to the work, “recognition” would likely be at the bottom if it were on the list at all. After over thirty years of being dispatched as an emergency responder, I have, usually, unwillingly, had my “15 seconds of fame” several times over. I feel it is time to share the limelight and let everyone know that the firefighter, the police officer or the paramedic would not be at the right place at the right time with the right stuff (including backhoes) if it weren’t for their dispatchers. The dispatchers that sit in often-windowless rooms, that never get to see the fruit of their labour and keep on doing what they do best; help people.

Sidebar

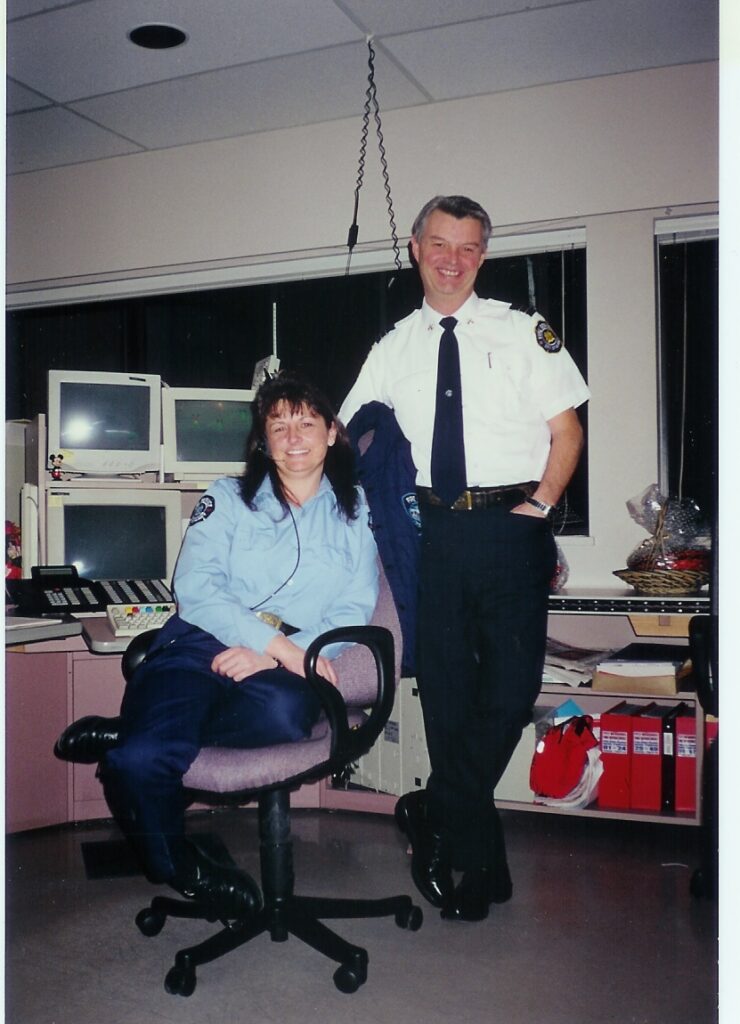

In 1998, I had a particularly outstanding dispatch crew. As fate would have it, we shared an incredible year filled with some of the most major and unique calls of my career. The crew “clicked” as a team like no other I have seen. Although it sounds a little trite, look up “synergy” in the dictionary and there would be a picture of “my three girls.” At the end of the year when regular yearly transfers broke up my team, they presented me with something they had written about themselves. One of t those three “girls” is now my wife and the piece is framed on our wall and will always be a reminder of that fantastic year. It was the inspiration for this article.

It is entitled “Who Are We?”

We are the voices that calm the mother when she calls stating her child has started a fire while playing with matches. Or the pot on the top of the stove has caught on fire.

We are the invisible hands that hold and comfort the person reporting their friend has been injured in a mountain climbing accident.

We are the friends who talk to the disgruntled asthmatics when they cannot breath during open burning season.

We sent help when you had your first automobile accident.

We are the ones who try to obtain the information from callers to ensure that the scene is safe for those we dispatch to emergencies – all the while anticipating the worst and hoping for the best.

We are the psychologists who readily adapt our language and tone of voice to serve the needs of our callers with compassion and understanding.

We are the ears that listen to the needs of all those that we serve.

We have heard the screams of faceless people that we will never meet, not ever forget.

We have cried at the atrocities of mankind and rejoiced at the miracles of life.

We were there, though unseen by our comrades in the field during the most trying emergencies.

We have tried to visualize the scene to coincide with the voices we heard.

At times we are not privy to the outcome of a call, and so we wonder…

We are the ones who work weekend, strange shifts and holidays. Children do not say they want our jobs when they grow up. Yet we are at this vocation by choice.

Those we help very seldom call back to say “thank you.”

We are thankful to provide such a meaningful service.

We are wives, mothers, sisters, aunts, nieces, granddaughters and daughters.

We are here when you need us and still here when you don’t.

The dispatch room is never empty, and the work is never done. We are always on call. The training is strenuous, demanding and endless. No two days at work are ever the same.

Who are we?

We are your crew.

We are “C” Shift, Battalion One Dispatchers.